A new exotic invasive pest ant species to Texas was found around Houston (Harris County), in 2002, and has begun to spread largely through human assistance. The ant has recently been identified as Nylanderia fulva (formerly Nylanderia sp. nr. pubens) and the new proposed common name is the tawny crazy ant (formerly Rasberry crazy ant) (Gotzek 2012). Currently, little is known regarding the biology of this ant. The Center for Urban and Structural Entomology at Texas A&M University has investigated numerous management strategies, diet preference, colony growth and immature development, and this species’ ability to translocate pathogenic microorganisms (see Danny McDonald’s dissertation: “Investigation of an invasive ant species: Nylanderia fulva colony extraction, management, diet preference, fecundity, and mechanical vector potential” and Jason Meyers’ dissertation: “Identification, distribution and control of an invasive pest ant, Paratrechina sp. (Hymenoptera:Formicidae), in Texas”).

A new exotic invasive pest ant species to Texas was found around Houston (Harris County), in 2002, and has begun to spread largely through human assistance. The ant has recently been identified as Nylanderia fulva (formerly Nylanderia sp. nr. pubens) and the new proposed common name is the tawny crazy ant (formerly Rasberry crazy ant) (Gotzek 2012). Currently, little is known regarding the biology of this ant. The Center for Urban and Structural Entomology at Texas A&M University has investigated numerous management strategies, diet preference, colony growth and immature development, and this species’ ability to translocate pathogenic microorganisms (see Danny McDonald’s dissertation: “Investigation of an invasive ant species: Nylanderia fulva colony extraction, management, diet preference, fecundity, and mechanical vector potential” and Jason Meyers’ dissertation: “Identification, distribution and control of an invasive pest ant, Paratrechina sp. (Hymenoptera:Formicidae), in Texas”).

What is an “invasive species”? (See the invasive species fact sheet)

Identification: How do I spot them?

Suspect tawny ants if you see a lot of ants with the following characteristics (see full listing of characteristics below):

- Appearance of many (millions) of uniformly-sized 1/8 inch long, reddish-brown ants in the landscape; foraging occurs indoors from outdoor nests.

(Click to see video of these ants found in the grass.) - Under a microscope you will find 12-segmented antennae, a petiole (1 node), an acidopore (circle of hairs at the tip of the gaster (abdomen)), and the ant will be covered with many hairs (macrosetae).

- Winged males (see image below) are needed for identification to species (see Gotzek et al. 2012)

- Ants that form loose foraging trails as well as forage randomly (non-trailing) and crawl rapidly and erratically (hence the description “crazy” ant).

- Ant colonies (where queens with brood including whitish larvae and pupae, See image on right) occur under landscape objects like rocks, timbers, piles of debris, etc. These ants do not build centralized nests, beds, or mounds, and do not emerge to the surface from nests through central openings.

A guide entitled, “The Common Ant Genera of Texas” (B-6138) is available at: http://agrilifebookstore.org. This reference will help identify the ants the the genus, Nylanderia, to which this invasive ant belongs. Several other species of Nylanderia occur in the state (see “The Distribution of Ants in Texas” at http://sswe.tamu.edu/PDF/SWE_S22_P001-92.pdf).

The description of the tawny crazy ant is very similar to the species description for Nylanderia pubens, the Caribbean crazy ant.

The Longhorn crazy ant, Paratrechina longicornis, may in some cases create massive, but localized numbers. These species look similar, but have marked differences. Paratrechina longicornis antennae and legs are significantly longer than that of Nylanderia fulva. P. longicornis mesosoma (thorax) is extended in length considerably, compared to that of the Nylanderia species. Although the use of color as an identification tool is not to be relied upon, the crazy ant is often jet black in color, especially when compared to the typically reddish-brown of N. fulva.

Submitting ant samples for identification: If you are a pest control operator and you suspect your client may have these ants, please contact the Center for Urban & Structural Entomology. Please send samples in sealed vials containing alcohol. Specific location data would be greatly appreciated (address, GIS coordinates). For more information on submitting samples: See Identification Request Form.

Impact: What do they do?

In infested areas, large numbers of tawny crazy ants have caused great annoyance to residents and businesses. In some situations, it has become uncomfortable for residents to enjoy time in their yards. Companion animals may, in some cases, avoid the outdoors as well, and wildlife such as nesting songbirds, can be affected. The cumulative economic impact is currently unknown.

Biting and medical implications to people, livestock and wildlife: Tawny crazy ants do not have stingers. In place of a stinger, worker ants possess an acidopore on the end of the gaster (abdomen), which can excrete chemicals for defense or attack. They are capable of biting, and when bitten, they cause a minute pain that quickly fades.

Nylanderia fulva, has been a serious pest in rural and urban areas of Colombia, South America. In this case, they reportedly displaced all other ant species and caused small livestock (e.g. chickens) to die of asphyxia. Larger animals, such as cattle, have been attacked around the eyes, nasal fossae and hooves. The ants also caused grasslands to dry out (dessicate) because the ants aggravated sucking insect pests (hemipterans) because the ants feed on the sugary “honeydew” produced by these plant feeding insects.

Electrical equipment: In areas infested by the tawny crazy ant, large numbers of ants have accumulated in electrical equipment, causing short circuits and clogging switching mechanisms resulting in equipment failure (see “Ants and Their Affinity for Electrical Utilities” at http://www.extension.org/pages/30057/ants-and-their-affinity-for-electrical-utilities).

In some cases the ants have caused several thousand dollars in damage and remedial costs.

Agriculture: Todd Staples, Commissioner of Agriculture, suspects this to be a potentially serious agricultural pest. These ants show likelihood of being transported through movement of almost any infested container or material. Thus, movement of garbage (see image B below), yard debris (see image A below), bags or loads of compost, potted plants, and bales of hay can transport these ant colonies by truck, railroad, and airplane. No information is available on potential yield effects in infested lands.

|

|

|

A. Rasberry crazy ants found in bag of leaves

Click to watch video |

B. Rasberry crazy ants found in trash can

Click to watch video |

Impact: What affect do they have on wildlife?

Wildlife such as nesting songbirds is irritated by the tawny crazy ants. Masses of crazy ants covering the ground and trees likely affect ground and tree-nesting birds and other small animals and cause wildlife to move out of the area.

The ants are even displacing red imported fire ants in areas of heavy infestation. However, after experiencing the tawny crazy ant, most residents prefer the fire ant.

Very little is currently known about the wildlife impact from the tawny crazy ants in the United States. If you observe any affect to wildlife, please report it to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department by submitting the “Wildlife Impact Report” form.

Biology: ID Characteristics & Behavior

Worker ant body characteristics:

Tawny crazy ant worker

Photo by Danny McDonald

Click on the image to view the major identifying characteristics.

- Coloration: Adult colony members, including queens, males and workers, are reddish-brown (although lightness or darkness of their body color may vary)

- Size: Worker ants are all similar in size (they are monomorphic), with a body length of 1/8 inch.

- Worker ants have long legs and antennae, although not as long as the crazy ant, Paratrechina longicornis, and their bodies have numerous, long, coarse hairs. The antenna have 12-segments with no club.

- There is a small circle of hairs (acidopore) present at tip of the abdomen (as opposed to the typical stinger found in many ants), a characteristic of formicine ants (found within the Formicinae subfamily).

Colonies:

- Tawny crazy ants can been found in enormous population densities. They are social insects that live in large colonies or groups of colonies that seem to be indistinguishable from one another.

- Colonies contain many queen ants (they are polygyne colonies), worker ants, and brood consisting of larval and pupal stages. Pupae are “naked” or without cocoons. They periodically produce winged male and female forms called sexuals, alates, or reproductives.

- The size of the colony infestations can be large and display super colony (unicolonial) behavior

Trailing behavior:

- Tawny crazy ants foraging trails are quite apparent (≥10 cm) and individuals forage erratically, hence the typical reference to “crazy” ant. Foraging trails will often follow structural guidelines (See image below), however, large trails can be found in open areas.

Nesting and nesting behavior:

- Rasberry crazy ant colonies can be found under or within almost any object or void, including stumps, soil, concrete, rocks, potted plants, etc.

- Nests primarily occur outdoors, but worker ants will forage indoors, into homes and other structures.

- Nesting occurs under almost any object that retains moisture.

Food and feeding behavior:

- Tawny crazy ants eat almost anything; they are omnivorous.

Tawny crazy ant tending aphids. Photo by Danny McDonald.

- Worker ants commonly “tend” sucking hemipterous insects such as aphids, scale insects, whiteflies, mealy bugs, and others that excrete a sugary (carbohydrate) liquid called “honeydew” when stimulated by the ants.

- Workers are attracted to sweet parts of plants including nectaries, damaged, and over-ripe fruit.

- Worker ants also consume other insects and other small vertebrates for protein.

- View a video by Bart Drees titled “Rasberry crazy ant feeding on oak aphid honeydew“

Seasonal abundance:

- Few worker ants forage during cooler winter months.

- In spring foraging activity begins and colonies grow, producing millions of workers that increase in density dramatically by mid-summer (July-August).

- Ant numbers remain high through fall (October-November).

Tawny crazy ant female alate Photo by Johnny Johnson

Tawny crazy ant male alate Photo by Johnny Johnson

Natural spread:

- No mating (nuptial) flights have been observed in the field, despite the periodic development of winged male and female ants, called sexuals, alates, or reproductives. This indicates that colonies spread or propagate by “budding” with breeding possibly occurring at/near the edge of the nest, creating new colonies at the periphery. Annual rate of spread by ground migration is ~20 and ~30 m per month in neighborhoods and industrial areas respectively and ~207 m/year in rural landscapes.

Distribution: Where are they found?

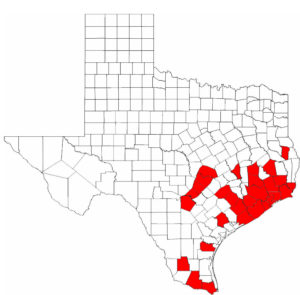

The tawny crazy ant has now been confirmed in the following counties: Angelina, Bexar, Brazoria, Brazos, Calhoun, Cameron, Chambers, Colorado, Comal, DeWitt, Fayette, Fort Bend, Galveston, Goliad, Gonzales, Hardin, Harris, Hays, Hidalgo, Jasper, Jefferson, Jim Hogg, Lavaca, Liberty, Matagorda, Montgomery, Nueces, Orange, Polk, San Augustine, Travis, Victoria, Walker, Wharton, and Williamson counties. New infestations are suspected beyond these areas of infestation. However, sample identifications have not been confirmed. This ant has the potential to spread well beyond the current range in coastal Texas. However, it is a semi-tropical ant and potential northern distribution will be limited by cooler weather conditions.

Management: What can you do for them?

Many of the typical control tactics for other ants do not provide adequate control of the tawny crazy ant. Because colonies predominantly nest outdoors, reliance on indoor treatments (see Rasberry Crazy Ant fact sheet or YouTube Video) to control these ants foraging inside structures is not effective.

Cultural control: At the foundation of any IPM strategy are cultural control methods beginning with the removal of harborage such as fallen limbs, rocks, leaf litter, and just about anything sitting on the ground that isn’t absolutely necessary. Cultural methods can also include altering the moisture conditions in a landscape. Crazy ants prefer humid, wet conditions so reducing the amount of irrigation, repairing leaks, and improving drainage should help.

Avoid spreading this species to new locations: Anything being moved from an infested area should be inspected for ants and treated before transferring it to a new site. Food sources should be eliminated or managed. Specifically honeydew producing hemipterans should be managed. Often, products containing the active ingredient imidaloprid or other systemic neonicotinoid are a good option for hempiterans.

Chemical control: Effective products involved with the treatments are not readily available to the consumer**. If you suspect your house or property is infested with these ants, call a professional pest control provider. After treatment, or when making multiple applications over time, piles of dead ants must be swept or moved out of the area in order to treat the surface(s) underneath.

Tawny crazy ant workers are not attracted to most bait products (see B-6099, “Broadcast Baits for Fire Ant Control“) and the most attractive product they are attracted to (Whitmire Advance Carpenter Ant Bait formulation containing abamectin (Label), see E-412 “Carpenter Ants“) does not offer enough control as a standalone treatment, and should be used in conjunction with contact insecticides. Maxforce® Granular Insect Bait is also highly attractive but has yet to be tested in the field.

There are treatments available for this ant that offer temporary “buffer zones” using contact insecticides applied to surfaces, such as those containing acephate, pyrethroid insecticides (bifenthrin, cypermethrin, cyfluthrin, deltamethrin, lambda-cyhalothin, permethrin, s-fenvalerate, and others) or fipronil. These treatments are often breeched within 2-3 months post application.

PCOs need access to an entire infestation in order to achieve an acceptable level of management. Otherwise, the population will rebound from surrounding, untreated sites within a month.

**Note for Professional Pest Management Personnel: According to the Texas Department of Agriculture, the following products have received expanded use approval through a Section 18 exemption from the Texas Department of Agriculture (TDA) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for the control of these ants. These are only available for use in counties with confirmed infestations of the tawny crazy ant. See product labels and supplemental labels for specific use directions: This exemption will expire on November 1, 2015.

| Termidor® | Section 18 Label |

| Talstar® | Section 18 Label |